Wallcharts

Claudia Jones – Journalist, activist and feminist.

When the Second World War ended in 1945, Britain needed to rebuild the economy for its citizens and also so it could better compete in an increasingly globalised world. To drive improvements in public services and industry, it sought to expand the labour force with immigrants drawn from the Commonwealth, a group of countries most of which had previously been ruled by Britain ‘at various times by settlement, conquest, or cession.’ Many of the early post-war immigrants came from former colonies in the Caribbean, like Jamaica, St. Lucia, Grenada, and Trinidad and Tobago. Their arrival also brought with it social tensions, and many were on the receiving end of widespread discrimination, racism, and harassment. A growing number of the immigrant community began to organise themselves to report on and campaign against these injustices. These pioneering activists led the way to changes in the law and censure of the perpetrators. The journey towards ending racial intolerance was and continues to be one met with social and political opposition.

In 2008 the Royal Mail issued a commemorative set of stamps called Women of Distinction. The set honoured ‘the achievements of six outstanding women.’ The person depicted on the seventy-two pence stamp was Claudia Jones, a journalist and civil rights activist. Claudia is best known for being one of the founders of Britain’s first major Black newspaper, the West Indian Gazette, and for furthering the social and political awareness of people of Black Caribbean heritage living in London in the 1950s and 1960s. Her legacy is particularly extraordinary when we consider that she only lived in the UK for nine years.

Claudia was born Claude Vera Cumberbatch on 21st February 1915 in Trinidad and Tobago, an island colony in the Caribbean that was ruled by Britain in what was then known as the British West Indies. Claudia’s parents left Trinidad in 1923 due to the economic crisis caused by the collapse in the price of cocoa, the main agricultural product of the islands, and emigrated to the United States. Like many immigrant families in America, life was tough. Claudia’s mother took a low-paid job in a clothing factory. She subsequently died at her workplace in 1924 from spinal meningitis, a disease that spreads easily in overcrowded factories with poor ventilation. Claudia did well at school, but when she was seventeen, she contracted tuberculosis, a lung disease associated with densely populated living conditions. She would thereafter be afflicted by poor health. Despite being academically gifted, she was characterised as a Black immigrant woman, and her options were limited. She found low-paid work in a laundry and worked in retail. She became interested in politics, and her experience of racism, sexism, and the poor treatment of workers in the harsh American capitalist system drew her to the radical communist ideas of political theorist Karl Marx. For Claudia, communist theory offered a more egalitarian solution than the exploitation and discrimination that she and her family had experienced living in the New York City neighbourhood of Harlem. In 1936 she joined the YCL (Young Communist League) and wrote for their newspaper. Over subsequent years she wrote about and campaigned on issues such as feminism, Black nationalism, communism, and struggles in the developing world.

The titles of some of her articles are an indication of the subjects and struggles that she was passionate about.

On the Right to Self-Determination for the Negro People in the Black Belt (1946), An End to the Neglect of the Problems of the Negro Woman! (1949), For the Unity of Women in the Cause of Peace! (1949), and American Imperialism and the British West Indies (1958) were all published in the American communist magazine Political Affairs. She also wrote many articles for other publications, including the newspaper she edited, the West Indian Gazette. Her articles frequently provided accounts of the discrimination and harassment experienced by the Caribbean community in London.

The end of the Second World War in 1945 saw the beginning of a new world order. The emerging superpowers were the USA and the Soviet Union, which had polarised political ideologies. The communist system, advanced by the Soviet Union, quickly spread. By the end of the 1940s, European countries such as Czechoslovakia, Hungary and East Germany were aligned to the Soviet system. China followed and countries in Africa and South America rapidly came under the influence of communism. The United States government was acutely sensitive to the growing spread of communism and became fearful of communist subversion within its own borders. Communist sympathisers like Claudia were frequently arrested and convicted for ‘un-American activities.’ After four spells in prison, in December 1955 she was deported from the United States. After Trinidad refused to accept her for fear that she would be ‘troublesome,’ she was granted entry into Great Britain on humanitarian grounds. Preceding her departure, 350 people gathered at the Hotel Theresa in Harlem to bid her farewell.

The Britain that Claudia Jones arrived in from the United States was a very different place for people of colour than Britain today. Prior to 1965 racial discrimination was not illegal in the UK. This meant that people were denied job opportunities, housing, education, admission to public venues and many other forms of discrimination because of the colour of their skin. The Race Relations Act of 1965 was a tentative attempt by the Labour government of the time to legislate against racial discrimination. The act made it a civil offence to refuse to serve a person, to serve someone with unreasonable delay, or to overcharge on the grounds of colour, race, or ethnic or national origins. Later amendments in 1968 and 1976 served to clarify and strengthen the rights of the victims of discrimination.

In 1956 Claudia was living at 6 Meadow Road, Vauxhall, in the London Borough of Lambeth. It was while living here that she co-founded the West Indian Gazette. The Gazette is now widely considered to be the first newspaper in Britain primarily aimed at an Afro-Asian readership. ‘The Gazette was vast and ambitious in its scope of reporting. Writers delivered thoughtful commentary on race relations in Britain, African independence movements, and the US Civil Rights Movement (CRM). The paper provided a linkage between the daily issues of West Indian immigrants in Britain and the global struggle against colonialism and racism.’With an estimated Caribbean immigrant population of 100,000 living in London in the late 1950s, the Gazette, which was published monthly, managed a circulation of about 10,000 copies. It struggled to break even, and Claudia’s health was in decline, exacerbated by the living conditions experienced in Harlem and from her time in prison.

Donald Hinds, a teacher and journalist who in 1966 wrote the celebrated book about Caribbean immigrants in Britain, Journey to an Illusion:The West Indian in Britain was a friend of Claudia’s. He met Claudia while working as a bus conductor, and she encouraged him to write his first piece of journalism. He said of her, “Claudia was a wonderful person, and it was only after she died that I realised that I was in the presence of history. If I were to call anyone my mentor, it would be her.” He credits Claudia with initiating his political awareness. Donald would go on to interview notable Black influencers like the American writer James Baldwin and Amy Ashwood-Garvey, a Jamaican activist, businesswoman and member of the editorial board of the West Indian Gazette.

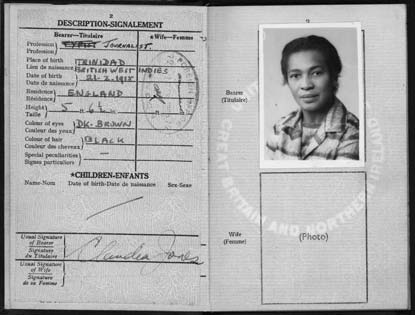

Prior to her expulsion from America in 1955, Claudia was issued with a British passport. In the section for describing the holder’s profession, she wrote ‘Typist,’ then crossed it out and with assurance wrote ‘Journalist,’ an occupation with a higher status. Persecuted and expelled for her beliefs in America and denied a return to Trinidad, perhaps she was nervous about being labelled an activist in her new country, or maybe she lacked the confidence to identify herself as a writer and campaigner, an occupation that could create meaningful change in a repressive world.

By the early 1960s her campaigning led to invitations abroad. She attended conferences in Japan, China and twice in the Soviet Union. Sadly, on the 25th of December, 1964, she died suddenly at home in her flat in North London from a heart attack. She was 49 years old.On the 8th of December 1965, almost a year after her death, the Race Relations Act 1965 came into force, a piece of legislation that came into existence because of the activism and journalism of people like Claudia Jones. Today her first home in Vauxhall and her last home in Camden are commemorated with English Heritage blue plaques, and there is a street in Lambeth named after her called Claudia Jones Way. According to her own instructions, her ashes were interred in Highgate Cemetery, next to the tomb of her hero Karl Marx.